Once upon a time, LEGO’s toy kingdom teetered on collapse.

It was 2003. LEGO faced a net loss of DKK 1.4 billion ($220 million) and was on the verge of bankruptcy. LEGO’s colorful bricks were scattered far and wide (over-diversification). Towers of blocks began to look like Rube Goldberg machines (product complexity). LEGO’s once-loyal subjects wandered, lost in a world of distraction (loss of brand identity).

Enter a new champion. CEO Jørgen Vig Knudstorp.

Knudstorp introduced a multipart strategic plan. Simplify the product line. Invest in innovation. Improve supply chain and manufacturing efficiency, and rebuild brand identity.

But strategy alone isn’t enough. People had to be moved.

Knudstorp knew this would be challenging. "Innovation is what LEGO is all about, but the company had a tendency to over-innovate. It is not always a good idea to innovate when you have a solid brand."

For strategy to live, ingrained organizational habits must change. "We had become too complex, too inward-looking, too driven by our own agenda rather than being driven by what the customer wanted. The company had lost its focus."

Knudstorp needed a narrative.

"I wouldn't say we were going back to basics, but we were going back to the core idea of what LEGO was about." Knudstorp’s story of the future was grounded in the past. "The brick is our main building block for the future. We need to protect the brick, protect the brand, and protect the people."

With strategy and narrative in place, the kingdom’s fortunes rose.

Under Knudstorp’s leadership, LEGO reduced its product portfolio by more than 50%. The company's revenue grew by more than 600% between 2006 and 2016. By 2017, LEGO became the world's most valuable toy brand, surpassing Mattel and Hasbro.

The narrative helps articulate the need for change.

Take Microsoft’s re-emergence. When Satya Nadella became the CEO of Microsoft, he introduced a new strategic narrative that focused on a "mobile-first, cloud-first" world. This narrative aimed to pivot the company's strategy towards cloud computing, enterprise services, and cross-platform experiences.

The narrative aligns with the organization’s values and purpose.

For Ford, this was a return to its roots. When Alan Mulally became the CEO of Ford, the company was struggling with a complex organizational structure, multiple brands, and a lack of focus on core products. Mulally introduced the "One Ford" strategic narrative, which emphasized unifying the company, streamlining the product portfolio, and focusing on the Ford brand.

The truth is the story we tell. Data is a prop.

Case in point, some widely circulating statistics. The first, “stories are 22 times more memorable than facts alone.” Often attributed to Stanford University marketing professor Jennifer Aaker. Or, when asked to recall speeches, “63 percent remember the stories. Only 5 percent remember any individual statistic.” This is a story cited in Chip and Dan Heath’s thought-provoking book, Made to Stick.

Convincing data of the power of story. Except neither is exactly true. Aaker’s 22 times fact isn’t validated by any research. Heath’s story is exactly that—a story, not a study. But both “facts” are often cited to prove the power of storytelling. Evidence itself that “truth”—what we choose to believe—emerges from story.

A story is a device that persuades.

A strategic narrative is, in fact, a collection of stories.

These stories stand between success and failure. They tell the need for change. People can clearly see the burning platform and the holy grail. The question of “Where are we going, and why?” is answered. A shared context and common language beds in. The strategy is translated from a synonymous word salad to a clear, concrete plan. Buzzwords are jettisoned, acronyms expanded. Heroes and villains come to light. Concerns are spoken of openly and addressed.

It’s a team effort, a journey, a quest.

Your strategic narrative has three acts.

Act I. Clarify the strategy. Building the strategic narrative and the message blocks.

Act II. Go from narrative to story. Curating a collection of stories and equipping an army of storytellers.

Act III. Bring the narrative to life. Socializing, measuring, and stewarding the narrative.

The worst crime of a strategy is that it is ignored.

Your strategy sits in an unaccessed PowerPoint file attached to a string of emails. The strategy had fifty minutes in the sun, lauded by the CEO at an annual kick-off, then everyone went calmly back to their day job.

Why?

It’s too confusing, too complex. No one has connected 30,000 feet to 10 feet. The strategy ignores cultural concerns, resistance to change, and pocket vetoes. Leaders don’t clear away the old work to make way for the new work. The strategy remains the job of one person or department.

To clarify the strategy is to translate the strategy.

That’s everyone’s job. Tease apart the confusing mish-mash of vision, mission, and goal. The why (purpose), where (vision), what (mission), and how (strategy/ plan) of it all. Get clear on what’s in and what’s out. What you will do, what you won’t do. What the end state looks like. Define the outcomes you’re working toward and what behaviors need to change.

End of Act I.

Simply christening your strategy a “narrative” isn’t enough.

You must turn your strategic narrative into a collection of stories. A creative mix of characters, conflict, context, continuity, and conclusion.

Those stories have a specific audience—the heroes of your story. That’s where the T-leaf and Motive triangle come in. The internal heroes—your team, employees, and other stakeholders—are dealing with the villains of change. Loss of control or status, clinging to the past, excess work, worries about our own competence, uncertainty, and surprise all stack up like gremlins.

These are all perceived, yet very real.

The traditional antidote is to show the business hockey stick. A rationalized plan that shows the current state intended actions and then a steady stream of good results on the way to a better future. Planning fallacies and excess optimism kick in. If there is conflict at all, it’s to declare that this will be “challenging” or “difficult.”

This doesn’t seem real. It is perceived as Kool-Aid.

A real story has real ups and downs. So too, your narrative has to embrace highs and lows. Acknowledge the difficulties ahead and the quest your heroes face.

Visual metaphors can help.

To do things differently, people have to see things differently. Literally. More, visuals allow people to see and discuss challenges in detail, without personalization. This is part of our process of developing a narrative—to show a map of change. This shows the strategy and the journey. It includes both where you are and where you are going, the challenges you face, and the new behaviors you want to embrace.

You want people to be able to see themselves in the picture.

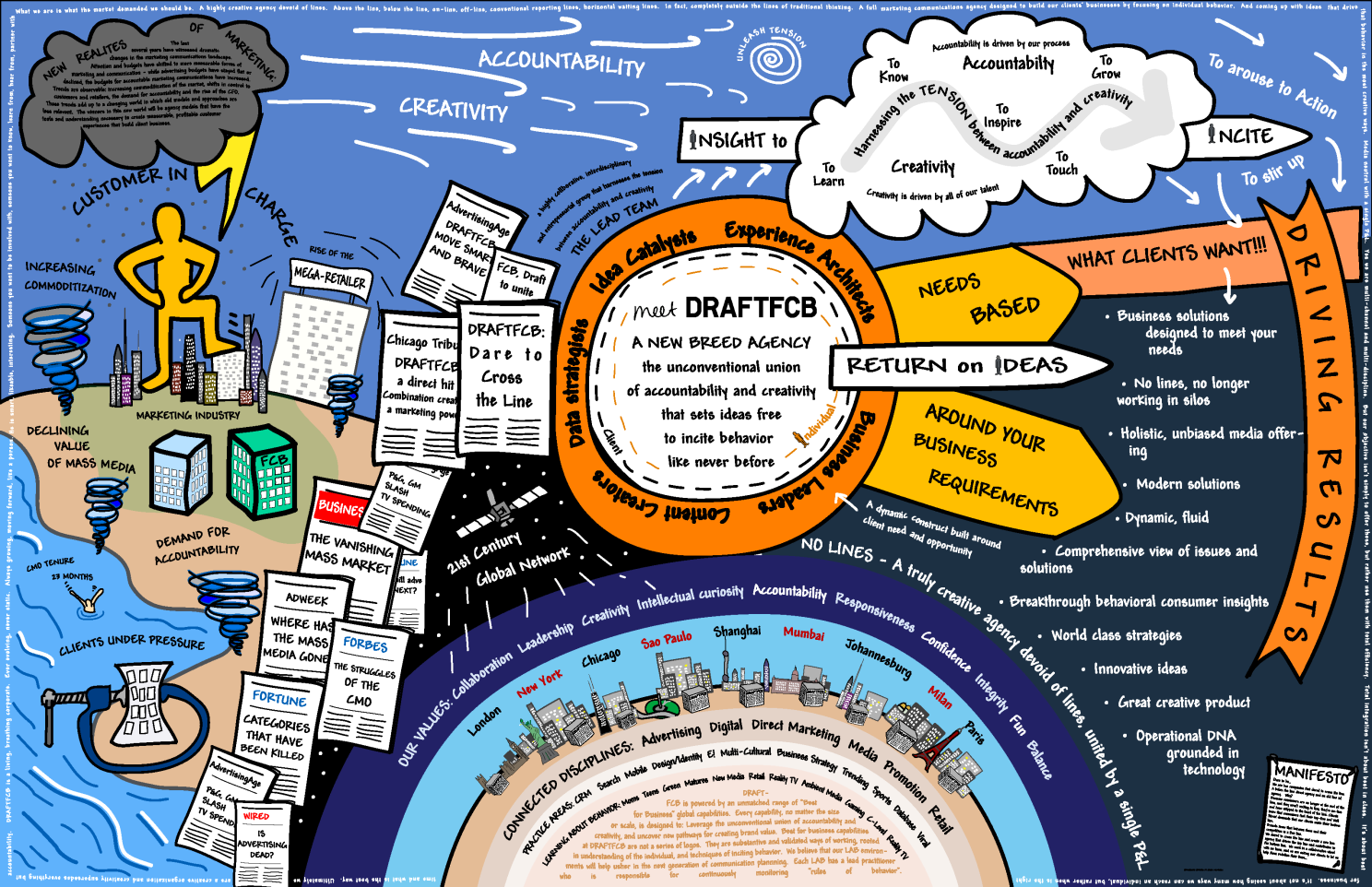

Years ago, two well-known marketing agency networks merged. Draft, a leading direct marketing firm, and FCB, a top-tier creative agency. DraftFCB was born. The strategy covered multiple pages of decks and slides. As a way of translating that into a strategic narrative, we created what became known as “the blue board.”

Styled after Keith Haring, the blue board became a totem for the new agency. Blown up and displayed as a ten-foot-high mural in offices around the world, it was the first thing customers (and employees) saw when they entered the building.

On stage at conferences and in town halls around the world, the blue board was a vehicle that carried DraftFCB’s strategic narrative.

Employees, who understood their presentation style; all trained to tell DRAFTFCB’s story and coached in rhetoric and connecting language.

End of Act II.

You might have heard of the legend.

John F. Kennedy (or Lyndon B. Johnson, depending on where you heard the story) is touring NASA headquarters and comes across a Janitor late at night. He asks him what he’s doing. To which the Janitor replies, “I’m not mopping the floors; I’m putting a man on the moon.”

That’s the goal of bringing the narrative to life.

You haven’t finished when your boss has the slides. You are on your way when every employee can see themselves in the picture. They understand how their daily work impacts the overarching mission. External stakeholders see and understand the narrative; the stories they tell add value to the company.

At this point, you don’t really control the narrative.

The strategic narrative is not a script. It’s more like a joke. One that, hopefully, everyone repeats. As people repeat their own version of the joke, the beats in the set-up are the same. The punchline is the same. But how each tells it depends on the context and the audience.

The net effect is that you are socializing the narrative through formal and informal networks. Andreas Hoffbauer, an expert in the social dynamics of organizations, sees strategy fail when we don’t tap into our informal networks. “Sometimes strategies fail because they are bad. But [more often] I see backlash because leaders did not build incremental buy-in, ensuring those most impacted by the change feel like they are part of the real conversation.”

Armies of advocates tell the story of change.

They help translate the abstract concepts of vision, mission, and strategy to the concrete; what am I doing today? How do we behave as a team?

Message discipline stewards the narrative.

This is not just keeping up the drumbeat of communication but ensuring that actions sync with words. This is a challenge for Mastercard. Their strategic narrative, The Mastercard Way, is a definition of how to create value, grow together, and move fast, a “how” as it reshapes its culture. Michael Fraccaro, Chief People Officer of Mastercard, wants to measure and incent that change. He is tying performance reviews and measurement (pulse surveys, etc.) to a scorecard of “what goals and targets people achieve, and how they do it.”

End of Act III.

Your turn. Don’t leave your strategy scattered in PowerPoint like a pile of LEGO bricks.

Build a narrative. Bring it to life.